1. We Will Fail to Solve Global Problems Simply By Looking at the World as It Is Today

Long-term risks identified by the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2020 were dominated by climate change, water shortages, and other environmental issues with a clear social impact. These challenges will no doubt sound familiar to you. Sadly, the proposed responses to these challenges are entirely inadequate. We may be delighted by promises by certain countries to become carbon neutral by 2050 or cheer on progress made by Tesla to popularise electric cars. Yet at the end of the day, many leading researchers see a very bleak future. Existing proposed solutions barely help the world as it is today and will do almost nothing to solve the strains our economies and society will be under in 2050.

To understand the world as it will be in 2050 and even 2100 we need to take a step back and look at the world with a 300 year perspective. The world is going through a global Great Transition from an agrarian to an urban industrialised society. The last time we saw such a change was in the transition from a hunter-gatherer to agricultural society. This Great Transition is already placing severe pressure on our planetary resources and environment, yet it is very far from complete. We can only develop meaningful solutions by understanding topics as broad as demographic booms, urbanisation, construction, energy, food production, and much more and the interaction between these topics. To help in this understanding, we have the 4Waves Approach.

What is the 4Waves approach?

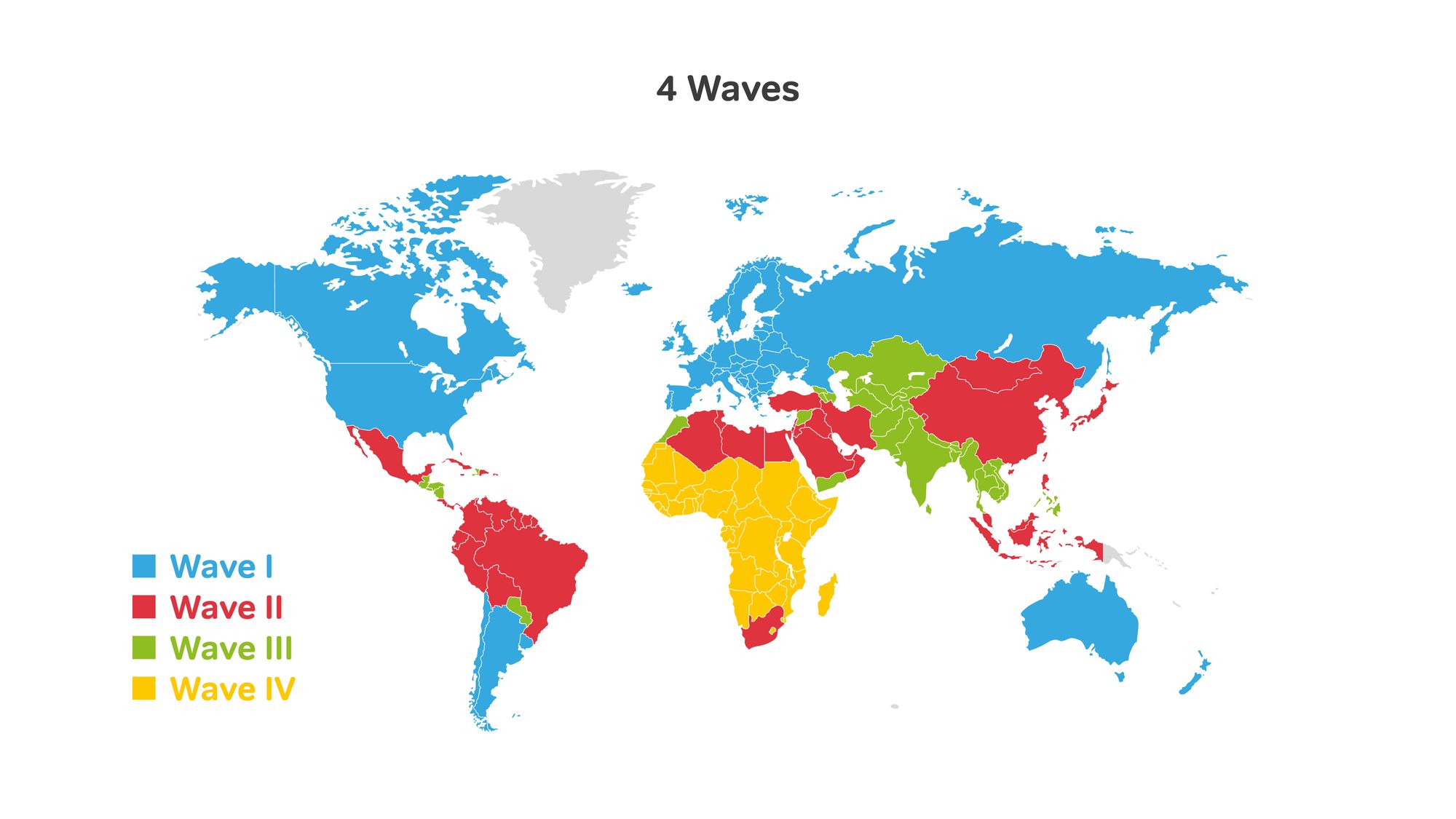

The 4Waves approach divides the world into four vastly different groups of countries or economies. This difference can be explained by one primary long-term trend – the Great Transition from an agrarian to an urban industrialized society. Usually, when we look at the world, we see where countries and societies are today and assume that things have always been this way. All too many of us consciously or unconsciously assume that Europe and North America have always been rich and populous, and that China and India used to be wealthy and are merely returning to their natural state. We do not assume that all countries are, in fact, simply at one stage or other of a Great Transition from an agrarian to an urban industrialized society. We forget that just as the world’s population grew by 4 billion in the 20th century, it is expected to grow by the same amount in the 21st century. We marvel at China’s explosive growth as it moves almost a billion people from the countryside to cities in just 50 years. But we do not look at Africa or many other less developed regions of the world, and see that they are simply at an earlier stage in the same development process that will see the equivalent of 3 new Chinas in the next 50 years.

To put that in other words, we cannot just decarbonise our energy production, food, production, etc. while maintaining production constant. We need to decarbonise all these sectors simultaneously at the same time as they are experiencing a major boom in demand. As we will cover elsewhere, it is all very well to increase renewable energy production even fivefold by 2050 as projected by the EIA. But those same projects see coal growing slightly and oil and gas growing rapidly as well to meet a growing demand of 50%. And that demand will not stop in 2050, it will continue to grow at least through the end of the century.

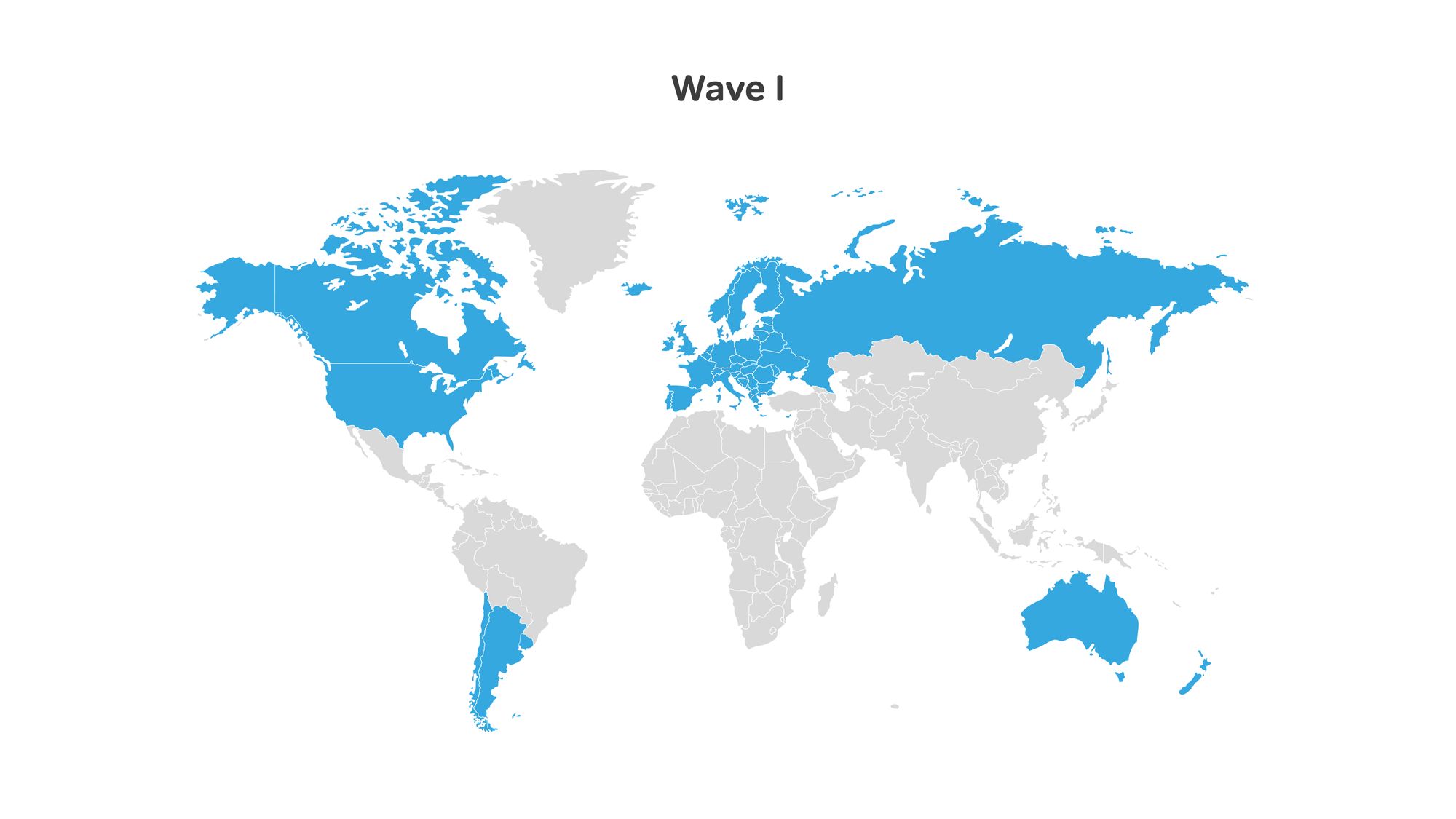

To understand why we can confidently predict growing demand, we can look at trends since the mid 18th, early 19th century. After 10,000 years of an agrarian-based society, the Great Transition to urban industrialized society began in the United Kingdom. The reasons why it began in Europe have been discussed and studied by many others, such as Jared Diamond. Regardless of the reasons, it spread throughout 1st Wave countries seen here on the map. These countries first showed the different stages of the Transition that other countries later started to follow.

This Great Transition has many aspects to it which help identify in which wave a country belongs to. There is a population boom. There is an economic boom. Countries start to use ever more energy as they move from manpower to coal power. There is a dietary transition. All this took place in the 19th and early 20th century for the 1st Wave countries. Then in the 1950s, the 2nd Wave countries began the same Great Transition, seeing the same growth in an even shorter space of time. The growth experienced by the 1st Wave countries, often referred to as “Western” countries, is different to growth in other countries only in that it started sooner. The 2nd Wave countries and the 3rd Wave at the end of the 20th century followed the same now predictable stages of development. The Transition of the 4th Wave of remaining countries has now begun.

So what happens when a country goes through a Great Transition?

When we look at human development from a 300-year perspective, we start to understand that the Great Transition is taking place everywhere, it simply starts in some places later than others. We also start to see that all countries go through very similar and predictable stages in their development. Understanding this helps us understand the increasing pressure that society and the environment is facing. There is no need in this introduction to go through each and every aspect of the Great Transition, but here are some examples. Firstly, for urbanization to happen, you need to produce steel, cement and construction materials to build cities and their infrastructure (construction boom). We are familiar with this construction boom in 2nd wave countries such as Brazil, China, and Mexico. Very soon we will be familiar with it in many other countries, particularly in the 3rd and 4th Wave countries. This production process demands not just tremendous amounts of raw materials but a lot of energy (energy production boom). And just as coal powered the first industrial revolution in the 1st Wave, it continues to power industrialization in countries in the 2nd and 3rd Wave. While projections show a rapid increase in the generation of renewable energy, overall energy demand is growing at such a fast pace that coal is projected to continue to power the development of the 4th wave countries.

Despite these many aspects of the Great Transition, there are three key indicators that can be used to quickly identify at which stage of the Great Transition a country finds itself. These are population growth, GDP per capita, and levels of urbanisation.

The first of these three indicators, is the so-called Demographic Transition. During this Great Transition from the agrarian to urban era, most countries have had a demographic boom. In 1900, there were 1.6 billion people. By 2000, there were 6 billion. By the end of the 21st century, most projections estimate that we will reach between 9 and 15 billion. Demographers see 5 stages to a demographic transition. A society will start with a stable population, the result of a high death rate cancelling out the impact of a high birth rate (Stage 1). As a society gains access to better healthcare and standards of living, the death rate is the first to fall. The result of this falling death rate, but still high birth rate is a rapidly growing population (Stage 2). The birth rate then starts to fall, as there are fewer reasons for large families. During this stage of the falling birth rate, the population still grows, but more gradually (Stage 3). Once the birth rate catches up with the falling death rate, then a society reaches a new period of population stability (Stage 4). It does not last though. The falling birth rate then collapses below the death rate meaning the population starts to shrink without immigration (Stage 5). Despite what many may think, all this happens regardless of culture or religion. Much like all other aspects of the Great Transition, the demographic boom (and bust?) is an entirely predictable global phenomenon.

The second key criterion for identifying whether an economy is going through the Great Transition is GDP per capita growth. We have become used to GDP growth every year. Our economies depend on it. Governments are thrown out of office if they fail to achieve it. But this was not the norm before the 18th century. Making exact estimates is hard. However, the best attempt to make such estimates is the Maddison Project. It estimates that in the 2,000 years leading to the 18th century GDP grew 0.01% per year and remained extremely low in all regions and all countries in the world. The Maddison Project estimates global GDP per capita pre-18th century remained around 400 to 600 dollars in today’s figures. This GDP per capita was the peak of the agrarian era’s potential. One of the most transformative results of the Great Transition is the growth from less than 1,000 dollars per capita to over 10,000 dollars per capita. An agrarian society simply cannot support such a GDP. 1st Wave Countries achieved this growth in under 100 years, 2nd Wave countries in less than 50.

If we take one of the modern world’s most famous economic growth stories, China as an example, we can see just how many economic miracles await us. Today China, like most 2nd Wave countries, has a GDP per capita of around 12,000 dollars (12,300 in 2016 according to the Madison Project methodology). But it started 50 years earlier with 1400 dollars per capita. GDP per capita figures hide the true scale of economic growth, because at the same time as increasing its GDP per capita 750%, it also more than tripled its population. And China’s GDP per capita is still only around a third or less of the level of 1st Wave countries who have completed the great Transition. Meanwhile, 3rd Wave countries are only a sixth or less on the way to completing the Great Transition, and 4th wave countries less than a tenth. In other words, we still have most of the world only part of the way to completing the Great Transition, and the world is already under stress.

Finally, levels of urbanization are another key indicator of what stage a country is at during the Great Transition. The Great Transition takes societies from 10% urban and 90% rural to the exact opposite. If we take China again as an example, as of 2020, over 60% of its population live in urban areas, a dramatic increase from just under 20% 50 years earlier. China now has 15 cities with over 10 million inhabitants. But that still leaves 400 million or so people we can expect to become urban dwellers. The 2nd Wave country continues its Great Transition. The third and fourth wave are now undergoing their transitions and by 2100 not one of the top-25 largest cities in the world will be in China, Europe, or the US.

This urbanization has far ranging impacts on the economy, the environment, and society. Among other things, there is a direct link between GDP and urbanization. Urban workers’ increased wealth allows them to buy more food like meat, milk, and vegetables which they then store in refrigerators and eat on dishes that they then wash in dishwashers. All these steps are so natural because they mean they progress for any family, for any person. Unfortunately, at the macro-level, this creates major challenges for humanity. And even if those same urban dwellers decide to drastically reduce their consumption, the resources and environmental costs already invested into building the cities they already live in and their infrastructure are not so easy to replace.

Is population growth the problem?

People often blame population growth for problems, such as Climate Change. This is actually only one part of the story. If we had 11 billion people living in the agrarian era, Climate Change would not be an issue. But it only takes 1 billion people living in the Urban Industrialised era to cause Climate Change. This is vital to any conversation about Climate Change. CO2 levels started growing above 280 ppm in the 1920s for the first time in 3 million years. That was just as a result of the 1st Wave countries’ Great Transition. When so many countries are still so early in the Transition, we can only expect already record levels to grow faster still.

To look at population growth another way. Recall that 2nd wave countries are only a third of the way through their GDP per capita growth and 3rd and 4th wave countries further behind still. With this in mind, the global population growing from 8 billion today to 11 billion in 2100 is less significant than 4 billion more of the world’s population becoming wealthier urban dwellers. Any benefits from reducing population growth would have required preventing population growth in the 20th century. Despite attempts to do so, those attempts failed to have any significant impact. Today it is far too late to focus on preventing population growth.

Frustratingly, debates around Climate Change was that it was focused on solutions to the world as it is now. Instead, he argues far greater changes are needed to prepare for the world as it will be in 2100, a world with 9 billion urban dwellers. We have to learn to green electricity production not at today’s levels, but at 2100 levels. We need to learn to build cities for billions of new urban dwellers in sustainable ways we have never seen before. We have to not just reduce fresh water and pesticide use in agriculture, but at the same time double or triple production. In this Great Transition, we are damaging far more than the climate along the way, we are overusing freshwater, provoking mass extinctions, running out of crucial resources, and much more.

This is not to suggest we should prevent growth in one or another country. He is merely emphasizing that the pattern of human development over the past 300 years has led to some very predictable results in growing consumption. This consumption is already placing pressure on society and the environment, and it is set to grow more. This path of development is showing no signs of stopping. In fact, it shows every sign of speeding up. This becomes obvious when looking at human development with a 300-year perspective, and acknowledging certain countries are not doomed to poverty; they are simply at an earlier stage in their development.

Nor is there much doubt that the third and fourth wave economies will continue to grow. If we look to PricewaterhouseCoopers projections for 2050 in terms of GDP PPP, we can not only see China double its GDP PPP, but also the even faster growth of 4th wave countries such as Nigeria, which is close to tripling in the same time period.

In conclusion

When seeking solutions to the problems facing the world today, we need to understand that the world is in the midst of a Great Transition from an agricultural to an urban industrial society. Most of the world has not completed this Transition, a Transition that will place ever increasing pressure on the environment and our societies. The 4Waves approach helps us understand how it is these pressures causing symptoms such as Climate Change and also the scale of the challenge facing us.

Over the next series of articles, we will look in more detail at different aspects of the Great Transition, specifically Demographics, Food, Urbanisation, Energy, Climate Change, and Technological Solutions. By the end of this series of articles, we hope that you will not only be able to recognise the signs of the Great Transition but also meaningfully apply the approach to your own investments and organisations.